The concept of deploying data centers in orbit periodically re-emerges in discussions about the future of digital infrastructure. The arguments are familiar: continuous solar exposure, reduced dependence on terrestrial land and water resources, and the perception of simplified thermal management. These claims often gain traction as pressures on Earth based infrastructure intensify.

Those pressures are real. AI workloads continue to scale rapidly, electrical grids face capacity and interconnection challenges, cooling and water usage are increasingly scrutinized, and the expansion of hyperscale facilities is constrained by regulatory and environmental factors. Exploring non terrestrial infrastructure is therefore a rational line of inquiry.

However, framing orbital data centers as replacements for terrestrial hyperscale facilities overlooks fundamental technical and economic realities.

From a systems perspective, space eliminates convective cooling entirely. Heat rejection must occur through radiation, which scales poorly at high power densities and requires substantial surface area, structural mass, and long term thermal stability. Power generation in orbit, while continuous in specific regimes, still depends on the deployment and maintenance of large solar arrays that degrade over time.

Economically, orbital compute introduces structural disadvantages. Launch mass remains costly, upgrade cycles are long, and exposure to radiation imposes ongoing reliability and performance penalties. Unlike satellites designed for decade long missions, compute hardware evolves rapidly, creating a mismatch between orbital lifetimes and technological relevance.

Latency further constrains applicability. While delay tolerant workloads such as batch processing or archival storage may be viable, latency sensitive applications remain poorly suited for orbital execution.

Where orbital infrastructure shows credible value is in narrowly defined, space-native roles. Processing, filtering, or buffering data already generated in orbit can reduce downlink congestion and improve mission efficiency. Cold storage, sovereign or isolated compute, scientific workloads, and preprocessing for Earth observation are realistic use cases when designed around orbital constraints.

In this context, orbit should be viewed not as a substitute for terrestrial infrastructure, but as a complementary layer with limited, well defined functions.

The broader value of this discussion lies in the discipline it enforces. Space systems demand clarity on workload requirements, latency tolerance, failure modes, and economic assumptions.

Orbital data centers are unlikely to replace terrestrial ones. When applied selectively and realistically, they may become an important component of a multi-layer digital infrastructure spanning Earth and orbit.

Article by @Roshmeet Chakraborty

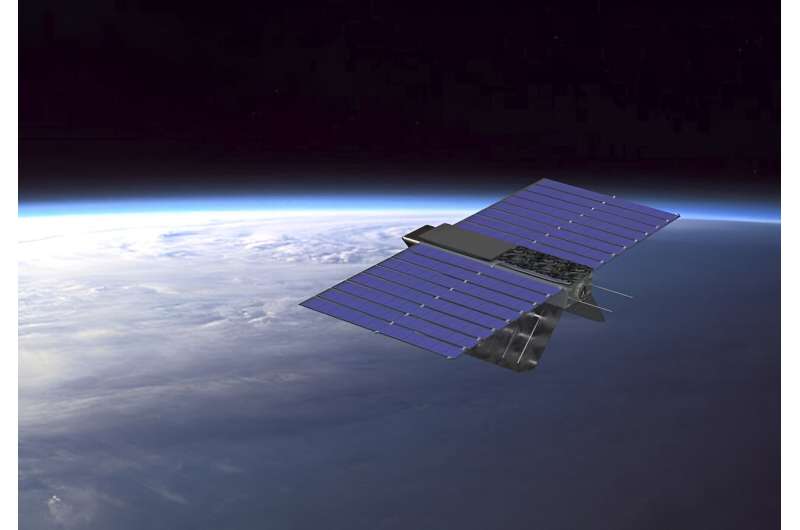

Image Credit: Lumen Orbit (now Starcloud)